Marcel Gascón GASCÓN BARBERÁ, Anja VLADISAVLJEVIC | BIRN. Bucharest, Zagreb

The death of Catalan photographer Jordi Pujol Puente on May 17, 1992 while he was covering the siege of Sarajevo unleashed a wave of sympathy in Barcelona for the Bosnian city that has continued ever since.

It was the spring of 1992 and the war had just started in Bosnia and Herzegovina when a young Spanish photographer with no prior war reporting experience landed in Sarajevo to take the pulse of the conflict in the city.

His name was Jordi Pujol Puente, he was 24 years old and he worked as a stringer for the Associated Press news agency and Avui, a young Barcelona newspaper published in the Catalan language to serve its readership in their mother tongue after decades of linguistic discrimination under General Francisco Franco’s dictatorship in Spain.

“We arrived in Sarajevo with the last flight [before the siege cut the city off from the rest of the world],” former journalist Eric Hauck told BIRN in an interview in Zagreb, where he now works at the Catalan regional government’s representation in the Balkans.

Hauck was friends with Pujol Puente and the Avui correspondent who was reporting on the Yugoslav war. The story of the cargo plane that flew all three of them to Bosnia’s capital is an indication of what kind of chaotic situation awaited them.

The plane had been seized by the Yugoslav People’s Army in 1991 in Zagreb, where it had just landed full of weapons to be delivered to Croatian troops. A year later, its Serbian owners were making a profit by renting it to the Sephardi Jewish community in Sarajevo.

With several flights to Belgrade and back, the plane evacuated the Sephardi Jews from the city that was by now under siege from the Bosnian Serb Army. And it took Pujol Puente and his friend and colleague to Sarajevo.

“Passengers were taking pictures of each other and some carried tennis rackets,” recalls Hauck of the atmosphere among those flying from Belgrade to Sarajevo before they boarded the plane.

One of Pujol Puente’s photos also captured the holiday-like, relaxed mood of the Jewish residents of Sarajevo after they landed in Belgrade.

“We all thought it [the siege] would last for a couple of weeks… but this was the last [civilian plane] landing [in Sarajevo] in many years,” Hauck said.

“When we just entered the terminal, the bombing started and the airport was not operational anymore,” he recalled.

At that point, Hauck, Pujol Puente and the rest of the journalists who were in the city at the time did not see the siege as the central event it was to become over the course of the war.

As the danger from the Serb forces besieging the city quickly escalated, however, they grasped the historical and symbolic significance of what was happening and committed themselves to tell the story to the world despite the risks it involved.

Although the bulk of their colleagues left following threats from Serb forces, Pujol Puente, Hauck and six other foreign journalists and photographers decided to decline the safe passage out of Sarajevo that was being offered by the city’s besiegers.

‘We were defending an idea of Europe’

On the one hand, Hauck recalls, they felt safer within the city than “trying to cross an insecure checkpoint outside without any guarantees”.

But there was another factor to their decision. They felt good among the citizens of Sarajevo who had not succumbed to the ethnic hatred that was fuelling tensions in the region. And they also felt it was their duty.

“We felt that we were not just doing our job but we were also taking part, with our work, in defending an idea of Europe,” said Huack, referring to the ideal of multicultural coexistence.

An encounter with Bosnian President Alija Izetbegovic’s media aide, who spoke to the journalists about the importance of their presence to dissuade Serb forces from launching a bloodbath to expedite their conquest of the city, contributed decisively to their sense of commitment.

The days they spent sending their reports using the single satellite phone they had and sharing everyday routines with residents of Sarajevo of all religions are well reflected in the photos that Pujol Puente took, which show a city that went on living as normally as possible under the shelling.

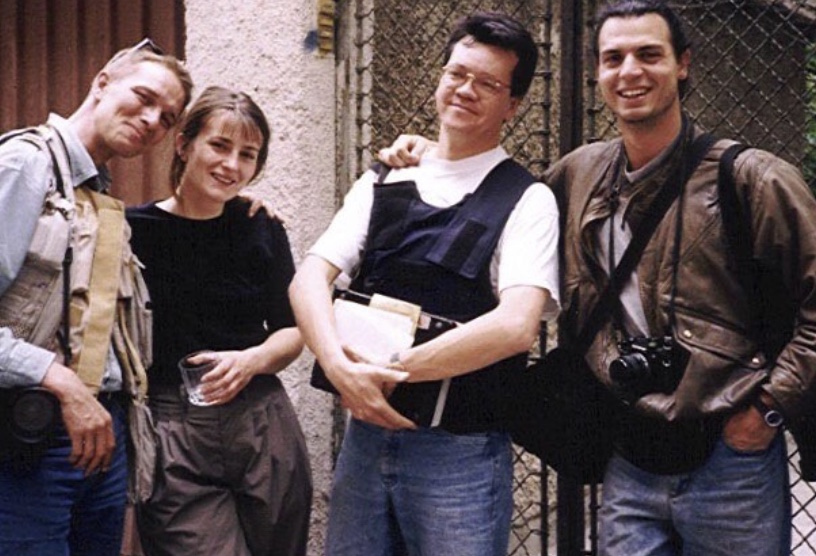

In one of the pictures, a hairdresser cuts a child’s hair. Another one features a working tram by a burned-out vehicle. Other images, taken by others, illustrate the camaraderie between the journalists. In them, Pujol Puente smiles at the camera with a hopeful expression of confidence. He has dark eyes and features and long, black hair – a look that earned him his nickname, Torero (bullfighter in Spanish).

Vicenc Villatoro is a writer and journalist and was the director of Avui during the war in Yugoslavia. He met Pujol Puente ahead of the photographer’s departure to the Balkans, and was amused by the name and first surname, Jordi Pujol, which are the same as those of the long-serving Catalan president.

“After he arrived in Sarajevo and started sending as pictures, which were absolutely consistent with the chronicles that Eric [Hauck] sent us, we had the feeling that his work was that of a very good professional,” Villatoro recalled.

“For us it was extraordinarily enriching from an informative point of view, which made it possible for our information about the Balkans to be original and exclusive, in line with the newspaper’s mission,” he added.

The death

As Hauck says, journalists get killed in wars. But Jordi Pujol Puente was killed on a most unlikely day.

“It was the first day of the siege with no bombing and in fact they were covering a demonstration by the citizens of Sarajevo against the war,” he explained, referring to Pujol Puente and his fellow photographer David Brauchli. The two men went together to the demonstration on May 17, 1992, while their reporter colleagues went to the presidency for an interview.

When Hauck and the Associated Press’s Tony Smith returned to the apartment they were sharing, they did not find the two photographers. They looked for them at the meeting points established in the security protocols they had, but with no luck. After hours of fruitless searching, they found Brauchli in a hospital and Pujol Puente’s body in the morgue.

While covering the demonstration, they had moved away a bit from the crowd, and then a mortar was fired in their direction. The exploding shell killed Pujol Puente and badly injured Brauchli.

Vicenc Villatoro found out about Pujol Puente’s death through a call by Hauck from Sarajevo. The same Sunday on which Pujol Puente was killed, Villatoro took his car and drove to the young photographer’s family home to inform his parents about the tragedy. “In those first conversations, which were many on that day and during the whole week, they refused to believe it,” he said.

Hauck and other journalists managed to take Pujol Puente’s body to Split, from where it was transported to Barcelona. “I remember the funeral, a stark sadness, with the family and the girl Jordi was dating and people from our newsroom,” Villatoro recalled.

A friendship of two olympic cities

Pujol Puente’s death was a crucial factor in making Catalans feel that the war was also theirs, Hauck suggested. People in Barcelona and the rest of Catalonia started paying more attention to the conflict and adopted Sarajevo as a symbol of goodness threatened by fanaticism and hatred.

The spirit of resistance and the loyalty to their own values displayed by Sarajevans made a deep impression on many Catalans, and a wave of sympathy and acts of solidarity was catalysed by Pujol Puente’s death.

Thousands of civil society groups sent humanitarian aid to Bosnia and many Catalan families took in Bosnian refugees. Barcelona’s eccentric and ever-ingenious mayor at the time, Pasqual Maragall, even added an ‘11th district’ to the ten administrative demarcations of the city – Sarajevo.

By declaring Sarajevo a district of Barcelona, Maragall removed bureaucratic restrictions from municipal humanitarian initiatives for the besieged city that would otherwise have delayed or aborted many of the projects.

Besides all this, Barcelona and Sarajevo shared an enthusiasm for the Olympic dream. Barcelona was preparing to host its first-ever Olympic Games in 1992, while Sarajevo had the same historic experience in 1984, when the city staged the Winter Olympics.

This connected the two cities even more and Maragall invited his Sarajevo counterpart Muhamed Kresevljakovic to Barcelona weeks before the 1992 Olympic Games started. Together with the International Olympic Committee, Barcelona’s mayor also called (unsuccessfully) for an Olympic truce in the Balkans for the duration of the Games.

The love story between the two cities that started when a mortar killed Jordi Pujol Puente in Sukbunar Street in Sarajevo still continues even today.

At Eric Hauck’s initiative, Sarajevo will be proposed as one of the host cities for the 2030 Winter Olympics as part of the Barcelona-Catalan Pyrenees bid to stage the Games, if it is successful.